“Give me liberty, or give me death!” – Patrick Henry

We continue our exploration of Contagious Ideas with a look at Open Access and the movement to reduce/remove barriers impeding access to scientific research and data.

Like many others, we are currently working from home due to the global pandemic. While doing so, the concept of Open Access has been brought into focus, as we’ve come to appreciate that we have taken our institutional access to scientific journals for granted. For example, the Web of Science database discussed during our citation investigation, is not viewable without an account.

The roots of Open Access are in the 1970s and 1980s, but interest in reducing the barriers to accessing scientific works grew rapidly during the 1990s with the proliferation of internet access and digital distribution. The term “open access” itself was not formalized until ~2002-2003 through several declarations including the 2003 Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing where it was defined as:

‘free, irrevocable, worldwide, perpetual right of access to, and a license to copy, use, distribute, transmit, and display the work publicly and to make and distribute derivative works, in any digital medium for any responsible purpose, subject to proper attribution of authorship’ and from which every article is ’deposited immediately upon initial publication in at least one online repository.’

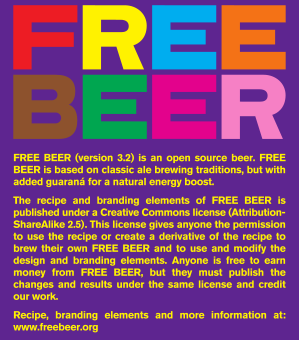

Freedom is central to any discussion of Open Access, but similar to any discussions of Free Software, there are important nuances related to the two concepts often conflated within the concept of ‘free’: ‘gratis’ (i.e. free as in beer) and ‘libre’ (i.e. free as in speech). Both are relevant to the discussion, as articles and data can be ‘free’ to read, without being ‘free’ to distribute/reuse.

There are some journals that are fully Open Access (e.g. PLOS ONE; for those wondering about the pronunciation, PLOS rhymes with ‘floss’), others provide Open Access to a subset of their articles, while still charging for access to the majority of their content. This has created a variety of terms used to classify the level of access, both with respect to journals and articles, as well as the particular stage of a publication that is considered ‘open’ for a specific article (i.e. preprint vs. postprint vs. published article).

- Gold: indicates that an article and its related content are available for free and licensed for sharing and reuse.

- Bronze: indicates that an article is free to read, but has no clear license regarding sharing and reuse.

- Green: indicates that self-archiving is allowed either through the website of the author/institution or an independent repository (e.g. arxiv.org).

So how does publishing scientific works as Open Access affect authors/scientists? It turns the typical business model of scientific journals on its head. Rather than a reader (either an individual or institution) paying a journal for access to an author’s work, the author pays the journal an article processing charge (APC) to allow all potential readers free access to the work. This obviously has major funding implications, academic laboratories typically run on very tight budgets, and even a single APC is a substantial line item comparable to a professor’s contribution to the annual stipend of a graduate student.

Open Access is not limited to the articles themselves, it can also refer to the data and code used within an individual article. Collecting data is expensive, so as datasets grow, it becomes increasingly important to maximize their value. Which is why some large research projects, such as the NSERC Canadian LakePulse Network plan to make all of their data publicly available through an online web portal upon the project completion.

In many ways, this is the beginning of a revolution in how scientific works are disseminated. It is still unclear what the implications will be over the coming years, and decades; however, it already seems that publishing under an Open Access model can increase impact and visibility.